Immigrants' struggles aimed at better lives

FACTS & FIGURES

Essay: What does poverty mean?

Understanding poverty is a different matter than simply defining it

by TAYLOR LIMA

“They’re kids, they don’t understand it and I can’t explain it to them, that we’re basically broke. It’s hard to see them go without things so that I can put gas in my car or buy groceries or pay rent. They’re the most important things in the world to me, saying no to them breaks my heart and I have to do it almost every day.” — Molly, a single mother

Poverty is much more than can be defined by any dictionary. It is a widespread issue, affecting billions of people in varying states of need. Poverty can be obvious, like a panhandler on the streets or a desolate neighbourhood occupied by boarded-up buildings and people lingering on their stoops, unable to find jobs. Or it can be invisible, a grotesque monster painfully trying to claw its way out from behind the neatly-put-together façade of a mother buying a toy for her kids, foregoing a past-due car payment. Whatever form it takes, there is one commonality between all three billion people worldwide who deal with poverty every day: it hurts. It is a pain unlike no other, a pain riddled with remorse, indignation and isolation that affects all other aspects of life. For those lucky enough not to face it — or for those who don’t have to face it in harsh degrees — it is a pain that is entirely unknown.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines poverty as “the state of one who lacks a usual or socially acceptable amount of money or material possessions; scarcity, dearth; debility due to malnutrition.”

For those who haven’t experienced it, understanding poverty is far different from defining it. The meaning of poverty is as different as the people themselves. For some, living in poverty means living below a designated income. For others, poverty means being without food, adequate clothing, medication for preventable diseases or adequate access to clean drinking water.

Absolute Poverty

In the United States, the Census Bureau defines poverty. According to the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institute for Research on Poverty, “The U.S. Census Bureau determines poverty status by comparing pre-tax cash income against a threshold that is set at three times the cost of a minimum food diet in 1963, updated annually for inflation using the Consumer Price Index, and adjusted for family size, composition, and age of householder.” A similar system, called the Low-Income Cut-Off, is used in Canada.

These methods are used to measure what is known as absolute poverty, defined by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization as “the amount of money necessary to meet basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter.” Absolute poverty does not measure a person’s quality of life, nor is it concerned with issues of inequality in a society. Its only concern is the amount of money needed for a person to have access to basic necessities; it does not care about a person’s access to societal and cultural fulfillments.

Because it was developed in the 1960s, many have criticized the system used to measure poverty in the U.S., calling it outdated and ineffective. New Jersey, for example, is one of the wealthiest states, with a poverty rate of 11.4 per cent. Because of overwhelming requests to assist low-income families, the United Way came up with a new way of defining poverty with the acronym ALICE — Assets Limited, Income Constrained, Employed. The ALICE model measures income from work as well as from government and charitable aid. The first ALICE report for New Jersey, released in 2012, showed that 30 per cent of New Jersey households did not earn enough to afford the necessities that constitute financial stability. That is a stark contrast to the official 11.4 per cent poverty rate assessed by the U.S. government.

Relative Poverty

For those who struggle with it, poverty means more than a lack of dollars in the bank. In an interview with NPR, economist and journalist Tim Harford described poverty as a social condition. “Poverty is partly about not having enough money to buy what society expects you to have,” he said. “If you don't have enough money to meet those social expectations, people will think of you as poor and you will think of yourself as poor.”

The World Health Organization has a similar description of poverty, defining it as “not being able to participate in recreational activities; not being able to send children on a day trip with their schoolmates or to a birthday party; not being able to pay for medications for an illness.”

This is what’s referred to as relative poverty. According to the European Anti-Poverty Network, “Relative poverty is when some people’s way of life and income is so much worse than the general standard of living in the country or region in which they live that they struggle to live a normal life and to participate in ordinary economic, social and cultural activities.”

Because of its relation to the standard of living, relative poverty varies from country to country. For those who live below the poverty line, it is relative poverty that affects them the most in their day-to-day lives.

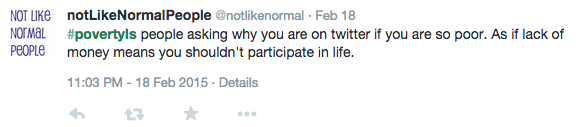

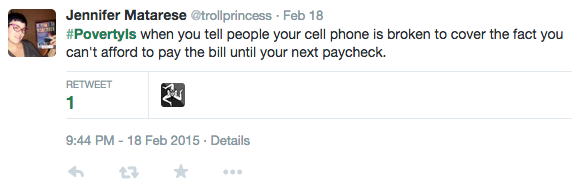

In 2014, NBC News and the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism produced a project asking people living in poverty to share their experiences on social media using the “PovertyIs” hashtag. Many who contributed expressed feelings of guilt and shame about living in poverty. Rebecca Vallas, Director of the Center for American Progress, chimed in on Twitter, expressing outrage at some of the welfare systems in place, “#PovertyIs being blamed for not having a savings account when [Supplemental Security Income] rules prohibit you from having more than $2,000 to your name.”

These stories express a growing problem in a world that now revolves around computers and smartphones. In order to feel like a productive member of society, and in order to fit in, it is expected that people have a smartphone, have a laptop, participate on social media. All of those cost money, money that could be used to buy food, put gas in the car or to make a dent in any outstanding debts. But if you don’t have an iPhone, you’re ostracized.

At the same time, when someone known to be living in poverty does have a smartphone, they are chastized for it. They are called greedy for using their money to purchase something that will help them feel like a normal member of society.

Molly, a single mother of two in Langley, who asked only to be identified by her first name, has experienced this feeling first hand. “I have two kids that I have to support,” she said, “but it’s not as simple as buying them food to eat and clothes to wear. They see their friends with iPads and they tell me that’s what they want for their birthday. It’s so hard to look your children in the eye and tell them that they’re not allowed to [fit in with their friends] because you’re too poor.” Molly works two jobs to support her children and is often left feeling defeated when she feels she can’t meet help them meet society’s expectations. “You feel like a bad mom,” she said. “They’re kids, they don’t understand it and I can’t explain it to them, that we’re basically broke. It’s hard to see them go without things so that I can put gas in my car or buy groceries or pay rent. They’re the most important things in the world to me, saying no to them breaks my heart and I have to do it almost every day.”

Other Types of Poverty

In his book Teaching With Poverty in Mind, author and former educator Eric Jensen talks about the harmful effects of poverty on children and their education. By identifitying six different types of poverty, he is able to demonstrate why poverty means so many things to so many different people. Along with absolute and relative poverty, he mentions generational poverty, which “occurs in families where at least two generations have been born into poverty.” He discusses rural poverty, urban poverty and a type of poverty that many have become unfortunately familiar with: situational poverty. This type of poverty is usually temporary and is caused by some type of event, such as a divorce, health problem or environmental disaster, or, as many experienced first-hand, an economic recession.

When the subprime mortgage crisis hit the U.S. in 2007 and the world’s economy took a turn for the worse, a tidal wave of people suddenly found themselves unemployed. Many were plunged into a state of financial panic after losing cushy salaries and sizeable retirement funds. Writer Jennifer Swartvagher and her family are all too familiar with the feeling. In a post published on the New York Time’s parenting blog Motherlode, Swartvagher describes turning over couch cushions and digging through pockets to scrounge up enough money for a gallon of milk and a package of cookies for her children. “We live in a beautiful tree-lined neighborhood,” she wrote. “Our struggle remains hidden to those around us.” When Swartvagher’s husband lost his job, the couple had to manage a family of 10 without the six-figure salary they had been dependent on. “My husband and I walk a tightrope in a constant balancing act, trying to figure out if we should pay the phone bill or put gas in the car,” she wrote in her post.

The Great Recession ushered in a new form of poverty, suburban poverty. The suburbs were once the home of financially comfortable middle-class families. When the economy tanked, its effects were felt everywhere, and cul-de-sac-filled neighbourhoods were no exception. The sudden burst of suburban poverty flipped the stereotype of what it meant to be poor on its head. Suburbia had long been the promised land of the American dream, where families could relax in their financial security and enjoy their picket-fence-lined lawns. But when so many of these families found themselves in situations like Swartvagher’s, suddenly the comforts of the suburbs brought about new challenges.

People who are impoverished in concentrated areas survive poverty together; they form communities where resources such as transportation and childcare are pooled. When poor people are spread out from each other as they are in the suburbs, they are spread out from the kinds of services designed to help alleviate the strains of concentrated poverty, such as subsidized housing or effective and affordable public transportation. According to an article by CityLab (previously The Atlantic Cities), in 2013 at a release event for a book on the subject, Louis Ubiñas, president of the Ford Foundation, drew attention to the fact that suburban poverty is the least visible kind of poverty of all. “We won't run into it on the subway or in the park,” he said. “We’ll drive past it on the highway.”